Jun. 04 2024

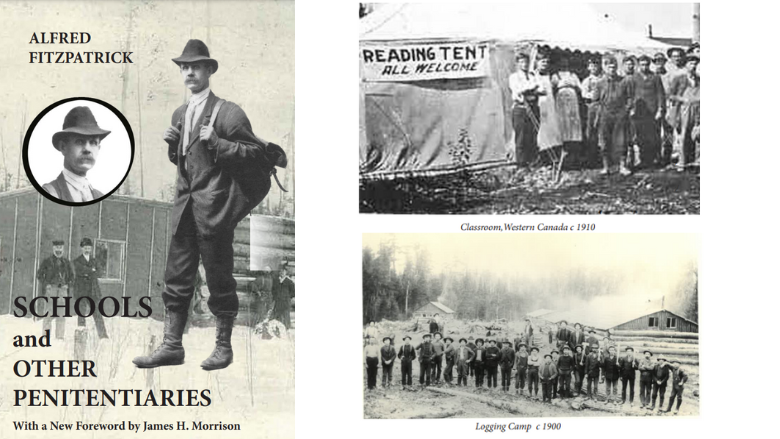

Jim was born in Nova Scotia and spent 40 years as a professor at Saint Mary’s University, Halifax. He has published many scholarly books, including three about the history of United for Literacy and Alfred Fitzpatrick:

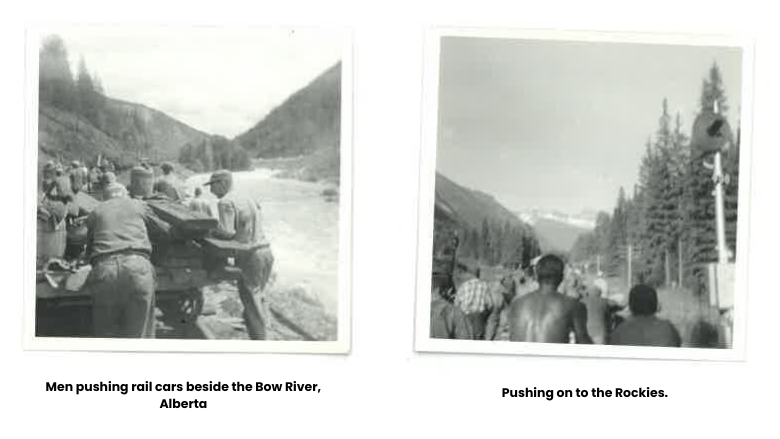

It fills us with pride to know that Jim started his long and celebrated career as a Labourer-Teacher with Frontier College in 1964 and 1965. Joanne Huffa, Communications and Alumni Coordinator, recently spoke with Jim about his time with the organization: as a Labourer-Teacher, member of the Board of Directors, and in-house historian.

*Answers have been edited for length and clarity.

How did you hear about Frontier College?

I was doing my undergraduate at the time, at Acadia. I’d been there for two years. My first and second year I’d worked with the naval training division, and it was not what I really wanted to do. It was nice because you made some money in the summertime, but it wasn’t what I wanted to do. I saw an advertisement up on the wall that advertised Frontier College, which said, “Hard work, low pay, all the blackflies you can eat. Apply to Frontier College for the experience of a lifetime.” That took me in, and I met with Bill Pierce, who was travelling at that time to various universities in Nova Scotia and beyond. I said, “I would like to volunteer.”

One of the things that Frontier College emphasized at that time was that you be in good physical condition because you were going into essentially—and for many university students this was the case—a very difficult physical environment, in terms of working 10 hours a day, 6 days a week. So you had to be physically fit, not just to do the work but to do what Frontier College wants you to do, and that’s to teach at night. So I passed that. I was brought up on the farm so hard work wasn’t something I was particularly concerned about. That was really my beginnings at the College.

What were you studying at the time?

I had just finished my second year of Physics and Math. That was going to be my double major. However, I got my marks in the summer while I was on the steel gang working on the railroad, and they didn’t go as well as I’d hoped. I kind of knew that was going to happen anyway. So I withdrew from that program and went into History and English, and continued on from there and did my B.A. in History in ’66 and then my Bachelor of Education in ’67. The summer of ’64 and the summer of ’65 is when I went out with Frontier College.

Did you have the same role for both years as a Labourer-Teacher?

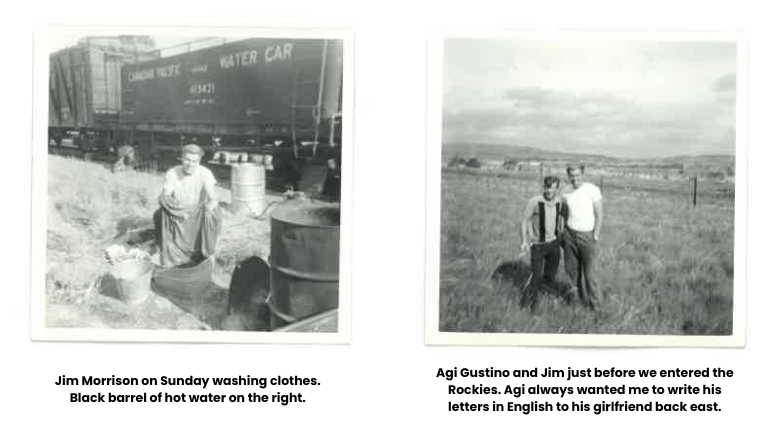

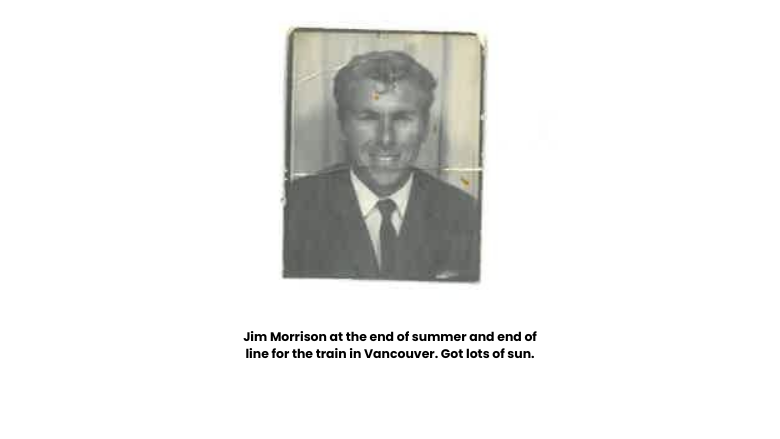

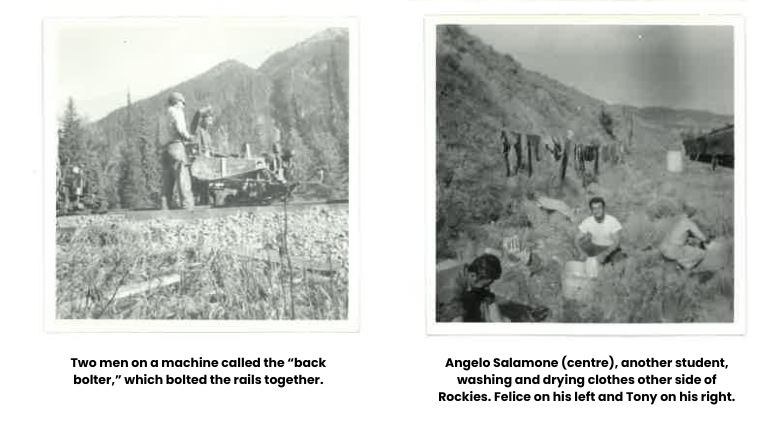

No. The first year I went out, I worked on the Canadian Pacific Railway on what they called the steel gang. We started in what’s now Thunder Bay, Ontario and worked all the way across to Vancouver over a four-month period. The steel gang was two crews that repaired the tracks that had either worn down or weren’t appropriate for large trains going through and so on. There were almost 200 men in boxcars on this train. There were well over 100 boxcars and sleeping quarters and places for cooks and food and all that kind of stuff. It basically consisted of a train pulling into a siding, and then there’d be a stretch of rail—maybe 5 miles, 10 miles, 15 miles—that had to be repaired or fixed up with new rails. So, the men would go out from there. We worked 10 hours a day, 6 days a week. Sunday was our off day. That’s when I had to organize recreation.

It was very challenging, physically. It was a good experience for me coming into a situation where I was teaching a class. I’d never done that before. I think that one of the things that was important in any Labourer-Teacher’s stint with the College was that you won the respect of the men by the work you did. And once you have that respect, after a week or two or three—sometimes longer—then you can start your classes. Because if you haven’t shown them that you can work on the railway, you’re not going to get them to come and work for you in the boxcars. That was my experience for that [first] summer.

The next year I was up in the Great Lakes Paper Company, which was in the well-named place called Dog River. We were working the pulpwoods on power saws and all those kinds of things. There was a fairly large Finnish population there, who were quite well known for their woods work. I spent that summer with them and taught at night. That was my second year at Frontier College.

I’ve heard that those first few weeks as a Labourer-Teacher could be quite difficult. What was your initial experience?

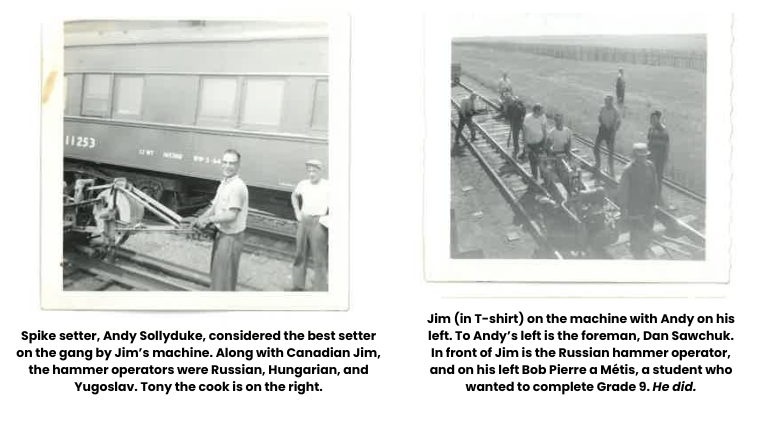

With the crew, the work matters, the size matters, if you look physically fit matters, because I was with another guy from U of T and, physically, he was unable to do what was expected of him to do. In my case, I was fortunate in the sense that, working for the steel gang, the first week or two I was wielding a hammer, driving in spikes by hand. That built up a few blisters on my hands. I have drawings in my diary that I kept about this (laughs). But after the second week, because of my size, they shifted me over to become what is called a spike hammer operator. There were five of us on each crew: 2 Yugoslavs, a Russian, a Hungarian, and myself. The machine was on wheels. It was driven by a gas engine, and it pounded the spikes into the rails, into the ties. So, your motion was coming forward and lowering it on the spike, forward again and lowering on the spike. Then you had what was called the spike setter. He was the guy bending over and holding the spike in place while you were driving it in [Jim raises an eyebrow and laughs]. So, you hoped like hell you didn’t smash his fingers. That was the kind of work I was doing.

By about the third week, once I’d got my wind back and lost a few pounds, I was able to start teaching. That was the beginning of what I was going to do for the rest of my life. I didn’t know it at the time, but what I wanted to do was teach adults or young adults and make it meaningful for them in terms of the kind of society they’re living in. That’s where history becomes important to me, right? So, that was good. I started tutoring. I had a young Métis fellow from Fort William who had his Grade 8. He wanted to get his Grade 9, so I tutored him. I had another fellow, an Italian immigrant, who hadn’t paid a lot of attention to me until this particular day about the third or fourth week in.

He said, “You have to help me!”

I said, “Help you with what?”

“My girlfriend crashed my car. I have to get the insurance money.”

So, I said, “Okay, let’s take a look and see what we can do.”

I could go crazy with anecdotes here, but the other thing was a fellow in his early 60s. He was picking up the wooden pegs that weren’t being used and putting them into storage. Physically, he wasn’t that well, but he needed work. He was out of Winnipeg, and this is what he did in the summertime to get him through the winter. Every day he would come in and ask me a question. One might be, “Are there really rings around Saturn?” and other kinds of questions. I said, “Wow, where’s this…?” And I didn’t find out until two weeks later that he was an avid reader, and he loved Reader’s Digest. So he was taking the questions from Reader’s Digest and coming and asking this university guy to see if he really knew what he was talking about.

I think that the lesson that was driven home to me was that, no matter who you are—don’t stereotype, obviously—but don’t assume. Here was a guy who worked very, very hard, but he had something up here [points to his head], as the vast majority of humans do, that wants to pull them on to more knowledge, to find out more about the world in which he lives. That was a nice lesson for me.

Once you had proven yourself, did the men come to you? And did you have your own space for teaching?

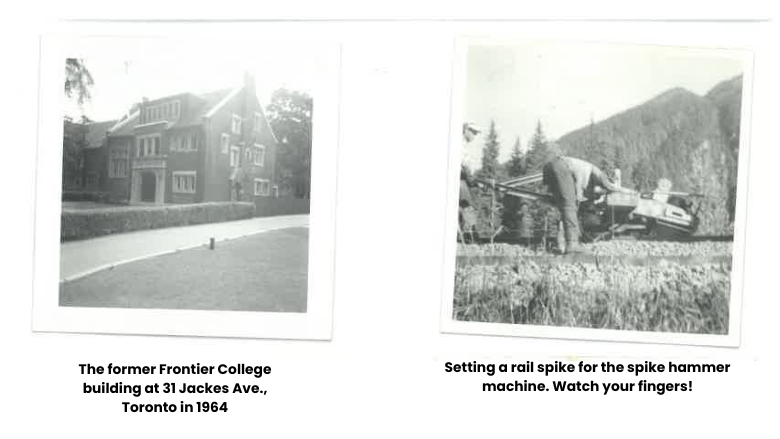

There was a railway car dedicated to classroom space. So when you go out, you were given a black rubber blackboard, chalk, a bunch of books—maybe Teaching Basic English or a bunch of novels—and CPR—and this was true of many of the camps, there was already a library car in the sense that there were already teaching materials there for you.

For the first three weeks, I slept in the boxcar; there were 12 men in the boxcar. When I became a spike hammer operator, they moved me to another boxcar so I would be with the other spike hammer operators, because these were the guys you were going to be working with and they have to know you. Of course, I learned some new swear words. I won’t repeat some of them, but nevertheless [laughs].

You mention that this work led you to become a teacher. Had you given any thought to teaching before this?

No. I was thinking of being a physicist in a lab. After my second year, labs bored me to tears. I know that’s why my marks went a long way down! I hadn’t really thought about teaching until I had that Frontier College experience and after a couple of years in History and English. The job situation was much better in the mid-to-late-‘60s than it would become, so History became my major. Then, when I did my B.Ed., in the initial faze, I said, “This is what I’m going to be doing.” I did practice teaching in some of the schools. But, as with Frontier College, something else came across my path; that was hearing about CUSO, which was Canadian University Service Overseas, which was a phenomenon that was, back in the day (not so much now. It’s changed greatly) a similar kind of thing. University graduates, whether you had a B.Ed or a B.A.G. (B.A generalist, as they called them), you would be recruited to go overseas to teach. So that fit very nicely into my plans, having done Frontier College, now I can carry out some of this in a totally new environment.

My dad said, “Why don’t you work for the civil service?” Not that he was disappointed in me, but I think he didn’t want to see me going overseas. I was with CUSO for 10 years. I went overseas to Ghana. I was in Nigeria. I travelled extensively when the opportunity presented itself. And I did my Ph. D. in African History. I’d done 2 years with CUSO, then I received a commonwealth scholarship to the University of Ibadan. I did my fieldwork and graduated in ’75. I taught at the same time.

What led you to return to Nova Scotia?

There were a couple of things. I had married by that time. My wife and I were married at Acadia in ’68. Then I had most of my Ph.D. studies at the University of Ibadan. In ’74, our first child was born, and we started thinking about family back home. We started thinking that my wife wanted to be a physiotherapist. She couldn’t do that in Nigeria. From my perspective, it was “my turn, your turn.” I had done my work, I had my Ph.D., now what do you want to do? She already had her first degree, now she wanted to do Physiotherapy. She would eventually get her Masters. And, of course, family. I come from a very close family in rural Nova Scotia, and you think in terms of ages when your family gets older.

Who was the Principal or President when you started at Frontier?

It would have been the President Eric Robinson in charge at that time. We had a bit of orientation. Obviously, we didn’t have a physical orientation, but we had a bit of an orientation in terms of pedagogy, or andragogy as it’s now called. I think we had about a week and a half where he took us through a language that we didn’t know anything about, and that was Inuktitut, and that was smart. This was something we hadn’t even heard of. He was very personable. I liked Eric a lot. He was very supportive, and he used to have the expression: “Frontier College is behind you. A thousand miles behind you.” [laughs]

Ian Morrison, who was President after Eric, was Program Coordinator by this time. My last year was ’65, and Ian was doing some of the travelling by that time, in terms of recruitment. But there wasn’t a large staff. The year before my first year, the secretary was Jessie Lucas, who is renowned at the College. She came up for retirement in ’63. I caught up with her before she turned 102! She would come to Board meetings in the ‘80s.

Did you stay connected with the organization between your time as a Labourer-Teacher and when you became a Board member?

I stayed in touch with Labourer-Teachers that I worked with. I met the later President of Frontier College Jack Pearpoint when I was in Nigeria. He was there at the same time. I would have gone out again as a Labourer-Teacher—and I was approached to be a supervisor of Labourer-Teachers in the West for the summer of ’66. But I got tied up in student politics and became president of the students’ council, and you had the summer in which to organize all this stuff. So that was my last official contact, and then I was gone. When I came back home [to Canada] in the late ‘70s, I looked up Jack, who had become President when Ian had departed. He asked me if I’d be interested in coming on the Board. I started on the Board with him, I guess it would be the early ‘80s… and I’m still there. [laughs]

How did you become United for Literacy’s official historian?

When I joined the Board in the early ‘80s, Jack Pearpoint was president. Because I’d had the personal experience…. It was a sideline for me. I’m not, by any stretch of the imagination, a professional Canadian historian. I’m an African historian. But you adapt. You do other things. So, Frontier College was important to me, but didn’t occupy 100% of my time. Jack said, “We’re coming up to our 90th anniversary, so it would really be nice if we had a publication.” They’d already hired someone, but it wasn’t going anywhere, so he asked if I’d do something with it. I said, “OK.” By 1989, we had Camps and Classrooms. It wasn’t—and here I am putting on my historian’s hat—it was a historical look at Frontier College, but it didn’t contain the kind of detail I would have liked to have seen on it because I didn’t have time to do another job on it.

Then, as we moved up to the 100th anniversary, I revisited Fitzpatrick’s book University in Overalls and did a re-edition of that. I didn’t change what he had written, but I gave an introduction to, I think I said, “the man, the mission, and the book.” I felt that he was key to why we are what we are. And how we can take him as an example. If someone ever said, “Well, who would ever think of doing that?” Well, Fitzpatrick did.

I stayed on the Board, and then when my term was up in 2000 I think it was, Bill Shallow was Chair of the Board. And he approached me and asked if I would serve as College historian. We drew up an agreement, and I agreed to do the Heritage Minute and ongoing research and the historical perspective and those kinds of things. Over time, we did the exhibit. And then as we moved into this time-period, I went with the biography of Fitzpatrick, which I thought was a good place to commemorate 125. I also wrote a short bio for young adults on Fitzpatrick.

How did the Heritage Minute happen?

The Heritage Moment [sic] came up in the late 1990s. We got the folks on board at Historica Canada. Not everything was successful in the sense that, what you do is give them whatever information you’ve researched and found, and they decide what they’re going to do with it. ISo, what they decided to do with it was, instead of recognizing Frontier College and having it in the forefront, they recognized Norman Bethune, which was fine. He was a Labourer-Teacher. But, it’s more than about Norman Bethune, right? We also got the Historic Sites and Monuments plaque. Little victories were there. The whole concept was always, “We have a past, and we learn from it.” Hopefully that’s been successful.

Do you have any thoughts as to why Alfred Fitzpatrick isn’t a household name?

We’re Canadians. [laughs] We’re very reticent about blowing our own trumpets. Fitzpatrick is interesting to me in the sense that he was certainly a Canadian in that degree. If you go through the photographs in the books that I’ve done—both Camps and Classrooms and the recent bio—he’s in the background. He certainly sought publicity that would highlight Frontier College, not Alfred Fitzpatrick. He had countless articles in the newspaper, but there was nothing on himself. It was always on the College and the importance of the College. He was a very ambitious, modest man. He very much felt honoured to be a Master’s student from McMaster University because all the other heads of colleges in Canada had graduate degrees, and he didn’t. But the whole strain of modesty is there. My fondest wish is that people will say, “Oh, yeah, we had a fantastic social activist. He may have been a little idiosyncratic from time to time, which I left in the book because I wanted to humanize him. I didn’t want to make him into this perfect figure. There are very sad aspects of his story as well.

He was very absent-minded. The one film we could have had of Frontier College in the 1920s, he left on a streetcar. It was never found. There was one copy of it and it’s gone up in flames by now probably.

Can you tell me a little about Alfred Fitzpatrick’s views on education and inclusion?

The expression for Frontier College was “I’m not here to teach you what you need to know. I’m here to teach you what you want to know.” Fitzpatrick was so far ahead of his time. His attitude towards women in work…. Whether they’re working in a fish plant in Nova Scotia or a travelling doctor, Margaret Strang, up in Northern Ontario. This idea that the student is learning what they want to learn, and you’re there to facilitate that learning. His attitude towards the First Nations communities. All of those things, for his time, are amazing.

Fitzpatrick thought outside the box. He said that we can send a woman out to work with Ukrainian women in Saskatchewan during harvest excursions. We can send a woman qualified as a doctor up to one of the homesteading communities up in Northern Ontario.

Can you offer a historical perspective on the name change from Frontier College to United for Literacy?

We became a College because we were degree-granting. We just didn’t take away the name College when we lost degree-granting status in 1931 because that was our identification. And to get the word out to people back then was a heck of a lot more difficult than it is today in terms of making those kinds of changes. United for Literacy, formerly Frontier College… people say, “OK, I know them.”

Where would you like to see United for Literacy go in the future?

To me, that comes around to the whole discussion of ChatGPT and AI. How can United for Literacy place itself in such a situation that we can encourage critical thinking when we look at the various messages that we’re being given? I don’t know the answer to that. Frontier College has played a very important role in bringing about broader literacy and helping people, when they read something, being able to understand what it says. At the same time, we’re now in a situation where we read, or hear, or see something…. How do we look at it critically and know if it’s true or not? It’s a big job. We can’t do that alone.

To learn more about United for Literacy's history, visit our page called "Our Story".

A special thank you to Jim, for taking the time to talk to us!